What can Mad Max teach us about the decline and fall of civilisations?

In popular culture, depictions of the future often fall into two possibilities. The first is a type of techno-utopia, free from war or want as depicted in shows like Star Trek. Occasionally, our protagonist faces a vexing time paradox or a whale loving alien megaship threatens to destroy Earth. In the end though, teamwork and compassion overcome adversity, leaving humanity free to continue its blissful existence. The second is a dystopian, post-apocalyptic hell hole like Mad Max or The Walking Dead. Zombies, nuclear bombs or ecological calamity have wiped out most of humanity. Only ragged bands of grim survivors remain, battling each other to the death for scraps of dog food and a tank of gasoline.

Pick your future!

Both scenarios make for great stories, but is either very likely? Predictions, as they say, are difficult to make. Especially about the future. The first scenario, a techno-utopia, is the easiest to dismiss. Requiring both new, fantastically dense energy sources and a complete change in how humans interact, it is improbable at best. The continuous spruiking on the internet of algae-powered lamps, non-existent fusion reactors or solar-roads as some sort of viable solution simply highlights the enormous gulf in understanding what a modern, industrial civilisation requires to operate. Yet the portrayed alterative, a rapid slide into chaos and anarchy as civilisation crumbles due to plague/financial crisis/environmental disaster is, if anything, even less likely.

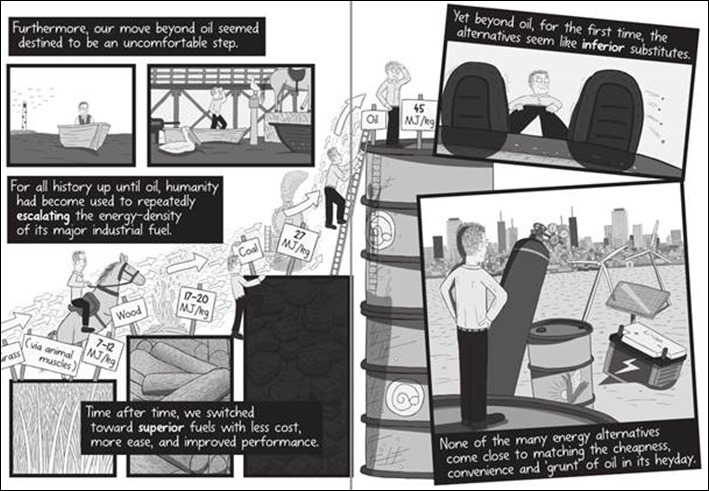

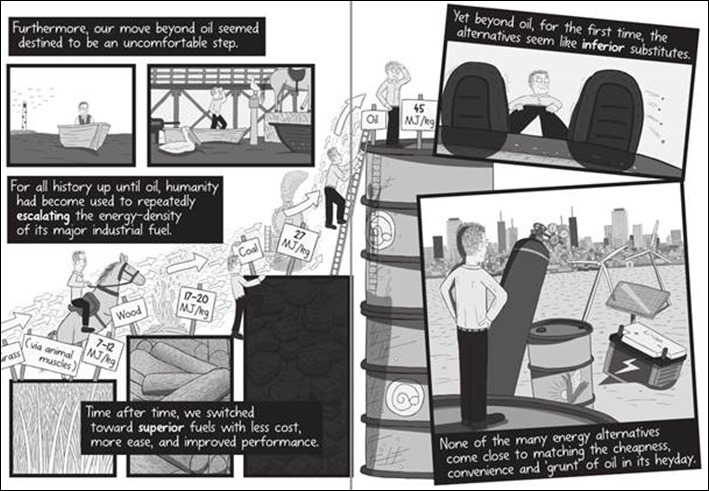

Can we do it again? Source: Stuart McMillen, Peak Oil

Over the past three centuries, humans have moved from grass and wood onto coal, then oil as the energy source of choice. Whilst highly unlikely, it is at least possible that something new might be found to fuel our energy hungry factories, trains and facebooks. On the other hand, despite the Earth being littered with ruins from dozens of major civilisations over thousands of years, there is very little evidence to suggest that any of them collapsed quickly.

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and it didn’t collapse in one either. Depending on where you start counting, it took over three hundred years of decline before the Visigoths came knocking at the gates. The same slow decline is evident for the Minoans in Crete, the Shang and Han empires in China, the Khmer Empire in SE Asia or the Babylonians in the Middle East. A 3rd century Roman slave or a 14th century Khmer peasant would have lived their day to day lives much the same as their parents. Even the quickest collapses, such as that of the Mayans, took almost one hundred and fifty years. It is only when summarised in text books that we see those eras as dramatic periods of contraction and turmoil.

Jon Snow Vs a volcano. Not how civilisations end!

So how do civilisations collapse? The list of failed empires is long and historians often have their own favourite theory. Volcanoes, droughts, climate change, warfare, changes in technology, resource depletion and cultural decline are all popular. Ignoring the root causes, which may differ, there is often a common path that each civilisation follows. Tonybee summarised these into distinct stages: genesis, growth, time of troubles, universal state and finally disintegration. Note that these stages can have blurred lines and overlap. For example the Roman empire arguably entered its 'time of troubles' in 49 BC when Caesar crossed the Rubicon, yet it continued to 'grow' its borders and wealth until the reign of Trajan in 117 AD, over 150 years later.

Tonybee also highlighted the formation and growth of an internal and external proletariat. He argues during the 'universal state' phase, a dominant minority begins to control the political and economic spheres. This self-reinforcing process leads to inherited privilege and the formation of a large, permanent and growing under-class which he called the internal proletariat. Meanwhile, outside the borders, an external proletariat looks on with envy at the riches and luxury even a poor citizen enjoys. Eventually, the pressure of the external proletariat outside the borders and internal proletariat within, crush a political system that no longer serves them. It is worth considering the resemblance of this scenario to the topical issues today of inequality, corruption, declining living standards and refugees. Indeed, the rising popularity of Sanders and Trump in the US can be directly attributed to these concerns.

It is fair to say that Hollywood and popular culture presents us with unrealistic depictions of societal collapse. It is unlikely we will see the compelling story of a Roman tradesman losing his job to a Celtic slave. Or the touching and heartfelt inter-generational drama of a poor family on Easter Island struggling with declining crop yields. However, there is a surprising franchise which does acknowledge at least some of the realities of collapse, even if only subtly.

The Mad Max series is well known for its action and outrageous costumes. The latest entry, Fury Road, is literally a two hour car chase across the desert. Yet despite their bombast, if you know where to look, the series has a lot to say about the gradual decline of civilisation and what rises to replace it. Just like Star Trek can use highly improbable human-looking aliens and wondrous warp drives to explore the themes of racial harmony or the nature of justice; if you scratch the surface just a little, and treat the irradiated wasteland as just a setting, Mad Max can have a surprising amount to say.

Who says Hollywood can’t do subtle?

In the first movie, our protagonist is a member of Main Force Patrol, a semi-official militia whom patrol the highways in modified XB coupes with their headquarters in an abandoned factory. There is a functioning government with railways and towns, but outlaw gangs are beginning to encroach and Main Force is fighting a losing battle. There is mention of a recent world war, and the general look is of economic and social decline (a nice side effect of the films miniscule budget). In one memorable scene, Max takes possession of a brand new V8 Interceptor, unfortunately it is the last to roll of the production line due to factory closures. Main Force will never again get new equipment. So whilst there are still jobs, hospitals and a police force, overall, things are looking grim. Unemployment is high and growing, swelling the ranks of the internal proletariat. Thanks to the rise of heavily armed motorcycle gangs it isn’t safe outside major cities anymore. Eventually, as small towns and regions become lawless, refugees (external proletariat) begin to flow towards the cities, increasing costs at the same time as tax revenues dry up. The scene is set for collapse!

In the second film, The Road Warrior, collapse of society is complete. Nuclear war has irradiated the coastal cities, leaving survivors to roam the wastelands. Max, now in a very battered Interceptor, stumbles across an outpost of survivors from the old days, struggling to defend a working oil rig against an army led by the charismatic sociopath, the Lord Humungus. He leads a group of bikie gang members, army veterans and social outcasts. The only interaction with society these people ever had is at the wrong end of a Main Force gun. They have no love for the old days since they received very little benefit from the old ways. They loot, pillage and destroy with relish, repaying decades of exclusion, both real and perceived. Those trying to defend the oil rig, who long ago outsourced their protection to people like Max, are easy prey. Ultimately, this movie boils down to some great car chases, but underneath is an important historical lesson of what happens to societies who farm out their protection whilst hoarding the benefits.

For hundreds of years the Romans persecuted and mocked Christians, who were seen as nothing more than a weird, sometimes dangerous cult. The teachings of Christ, with its focus on the meek inheriting the Earth, eternal salvation and so forth became very appealing to the millions of slaves and downtrodden in Roman society. As the internal proletariat grew, the tried and true solutions of lion feeding and crucifixions became less effective. Riots, insurrections and civil wars became more common. Eventually, with Roman society weak and fraying, the Emperor Constantine officially converted to Christianity, but it was too late. Externally, Rome now only controlled a fraction of its former empire. Internally, centuries of tradition and creed were being replaced by the latest and greatest religion.

As Rome pulled back from the regions, new rulers rose to fill the power vacuum. They needed to be charismatic, so men would follow them. Ruthless, to grab power in the chaotic aftermath of Roman withdrawal and pragmatic, to hold onto their hard-won spoils. In short, they were warlords. To provide an aura of legitimacy, many of them adopted Roman customs and titles, after all, the local population would still consider themselves Roman (post-Roman Britannia was run along more or less Roman lines long after the legions left). The rank of Duke, denoting the ruler of a duchy in medieval Europe can be traced back to the old French term, duc, which is from the Latin, dux. In the empire, the rank of Dux referred to the commander or governor of frontier troops in the provinces. Such an individual would be well placed to stay behind and take over as the empire shrunk. That the term duke is still in use nearly a thousand years later suggests that many of them tried this and succeeded. And it still works today, consider the rise of Putin, a former KGB officer, during the break-up of the Soviet Union.

What’s the difference?

The first two Mad Max films were set during societies decline and collapse. The next two show what rises to replace it. In Fury Road, we visit the Citadel, an immense fortress that sits atop a water aquifer. It is ruled by Immortan Joe, a former Army colonel, turned outlaw bikie gang leader, turned despotic ruler. His army worships him and the cult of V8, if they die in battle, eternal life in Valhalla awaits them, all shiny and chrome. It is all great fun and may seem unlikely until you remember that former army officers and weird cults is usually what moves in to replace a retreating culture.

Despite the presence of these details, the Mad Max series should not be held up as a possible future, the portrayed collapse is at least an order of magnitude too quick and severe. Yet, its portrayal of the proletariat, declining society and the rise of fringe cults and strongmen to replace what’s lost is historically accurate. When one considers the success of Putin, Trump and other ‘strongman’ politicians across the world, these themes and ideas have a modern significance. Indeed, to the students of history, their success is a troubling indicator of exactly what phase of decline our society can be placed.